“You had me at hello.”

It sounds simple, doesn’t it? We come home and see our loved one, thinking that it will be a reprieve from the stress of our day. Why then do so many couples struggle with greeting one another? I have noticed that rather than feeling relieved, some feel the pressure of meeting needs or getting needs met. Many couples report feeling as though it is a “competition”.

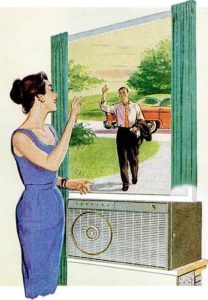

Things are not as simple as the old days (see picture above), when men worked and wives stayed home. While not a fan of that template (it had its own problems!), I suspect that the rigid structure made it simpler to attend to each other at times, or at least simpler for men to get their needs met! Men brought home the bacon, and women fried it up in a pan. (Again, not a fan!)

Nowadays most households have both partners working, and often with opposing schedules, so who attends to whom? If both are bringing home the bacon, who does the frying? Does it have to be a tug-of-war? Is it possible to greet one another in a way that reconnects and refreshes rather than it feeling like a task? Yes it is! And it has to do more with your intention than your actions.

IT DOES NOT HAVE TO BE A COMPETITION: I often hear how tired people are–the demands of work, family, and relationship can contribute to all three feeling like tasks, rather than the first serving the latter two. If you have a job where you are meeting needs for others all day long, it is reasonable to want your needs met when you get home! But is that what your partner is for? What about their needs, their tiredness? Does it have to be YOU vs. THEM?

If viewed as a competition, the choices made will serve the individual. There is nothing wrong with getting individual needs met, but many couples favor this and neglect the needs of the other and the relationship. Conflict can happen if one relies on the other for ALL their needs, seeing the relationship as a vehicle for getting some of the things that they could and should be providing for themselves! If both partners are doing this, it can cause a sense of competition to get what is wanted, with the relationship and connectedness suffering as a result.

Needing another is NOT co-dependence! We have evolved to prosper from healthy inter-dependence, which means that as I attend to you, I attend to myself. “Need competition” can only exist in relationship when a couple is disconnected, because in this state the main concern is protecting the self–there is no “relationship” to fight for. When you are connected, the relationship is as much a concern as individual needs, so attending to the other and the relationship means you both win!

WORDS CAN GET IN THE WAY: Granted, modern living can make it difficult to do this, especially if our individual needs have been neglected all day long. What can make this easier?

If you are in a relationship, how do you greet your partner(s) when you get home? Is it a kiss on the cheek and an inquiry into how their day was? Do you launch into your day, with the expectation that they will be interested and engaged in listening to you? Do the words you say often end up looking like a demand or a criticism? Are you interested in each other?

Words can get in the way of connecting meaningfully. I notice that the things many couples talk about are about everything except what would connect them: their boss, the traffic, the kids, the plans for tomorrow. All of that can wait until you actually spend some time finding out who the other is in this moment and what is going on with them, while letting them know the same about you. How is this done? Without words, sometimes! I regularly assign my couples clients the exercise of GAZING, a simple and effective way to connect to the other without talking. You simply spend a few minutes looking into their emotional world. (Click HERE for a link on how to do this exercise.)

If you want to use words, I suggest getting curious about the other who you are seeing “anew”. Some questions you could ask include: What did you find out about yourself today? What have you been waiting to share about your day? Did you talk to anyone interesting today? Where are you at right now? You can even use the time-worn “How are you?”, if you are willing to really hear their answer! Let your interest guide you as you consider what you really want to know about this person who you haven’t seen all day. Think about the effect it would have if you set aside the thought that there were exactly the same as when you last saw them.

ATTENDING TO SELF AND RELATIONSHIP: They say that how we think about reality defines our experience of reality. If you see your relationship as a place where all your needs must be met, then it is likely that you will spend a lot of time being resentful and disappointed. If, however, you see your relationship as an entity with needs of its own, apart from individual needs, then your approach will be relationship-serving as well as self-serving. The relationship will refresh you.

The result is to keep it feeling new, to stay away from the thought that there is nothing more to learn about your partner and nothing new to offer them. I see the greeting as a way to ask one another, “Who are you now?” If you ask this with genuine interest, you might be pleasantly surprised by the answer, and find yourself looking forward to reconnecting!

NOTE: Connection doesn’t always happen simultaneously. It helps to be curious about what the other needs before diving back into the relationship. How these needs are communicated is key, however. If you are one of those people who needs to “unwind” for 30 minutes before you listen to your partner, then let them know that, with the added information that you will be available in 30 minutes. Don’t leave them hanging! This is a way to take care of yourself AND take care of them!